For most of the founders I find in my circle, the urge to talk about what they are building is almost as strong as the urge to keep it vague and secretive. In contrast, I like to talk about whatever I’m working on. In fact, this open culture is a necessary part of my problem-solving process - I need people to bounce ideas off of, all in spite of the advice of my most successful friends and colleagues. I’m starting to think this approach is wrong. There is inherent value in building secretly.

Intuitively, total secrecy shuts out a powerful tool: the insights of others. These insights can be used in three ways: to test out a basic understanding of the core idea, to benefit from the experience of others, and to highlight a new way of thinking around a topic. While testing the core idea can be done by clear documentation (or investment in a rubber duck), the second and third benefits have no real substitutes. The experience of others can provide insights into what they have seen fail and succeed, and with proper interrogation, those insights can become actionable things to take away (buying a lottery ticket is an example of ignoring the experience of others). Lastly, being exposed to a new way of thinking is a feeling many of us benefit from invisibly within our societies. The world where we all think similarly does not include both Linux1 and Microsoft. The insights of others provide the necessary resources for a natural selection of ideas to take place as ideas get exposed to the experiences, and thinking of other people.

Does building secretly mean we sacrifice the benefit of the natural selection of ideas? I don’t think that’s true, but to understand why we must dive into how actual natural selection happens.

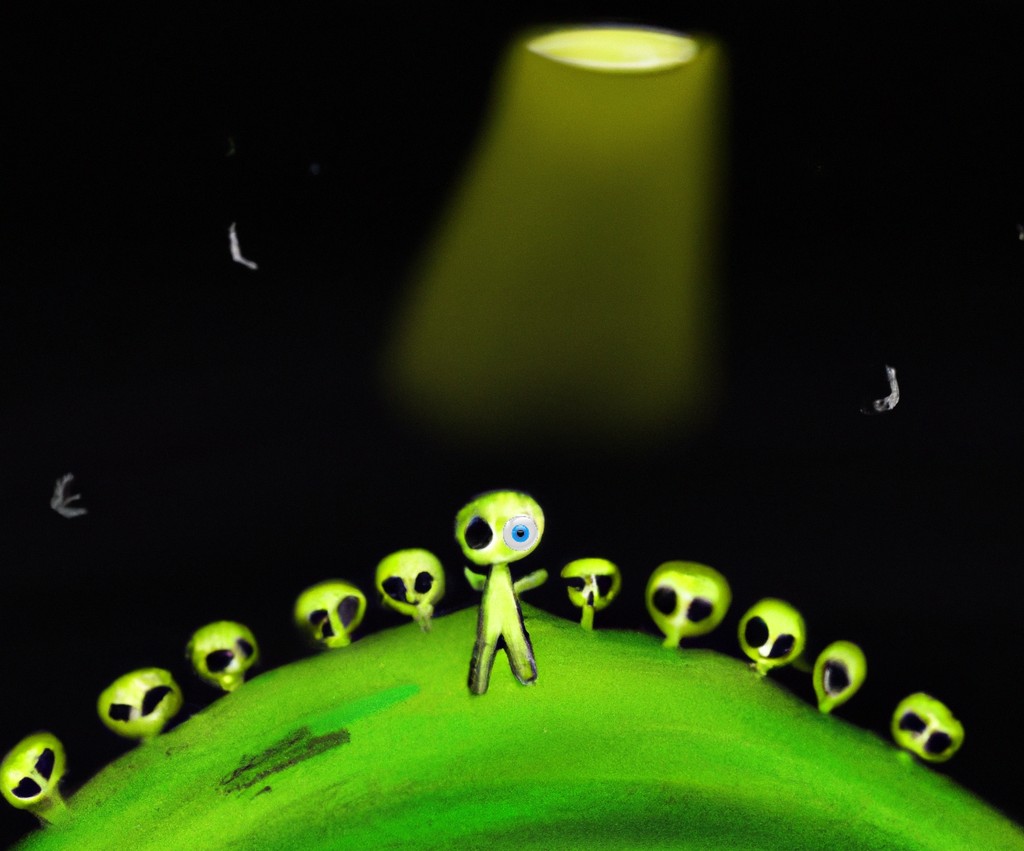

In biology, natural selection needs two elements: genetic mutations (i.e., a change) and environmental selection of beneficial changes2. These are necessary conditions but not sufficient. Not only does a beneficial mutation need to be useful and get selected, but it must also be able to stay in the population and not get washed out. To see what this means, consider a one-eyed alien (call him Craig) in a colony of naturally blind aliens. Craig has a very large advantage to survival compared to his peers because he can see. But in order to pass this on to his children, his kids must inherit the Craig-mutation, and not the genetic equivalent from his blind baby-mama. Repeating this process many times most likely “washes out” the Craig-mutation from the genome3. The only way the Craig-mutation can survive is that the benefit the gene provides outweighs the chances of the mutation being washed out of the species entirely. In other words, the usefulness4 of the Craig-mutation must outweigh the “washout” probability imposed by reproducing with people without the mutation.

|

|---|

| The birth of Craig - Image generated with DALLE-2 |

In genetics washout probability is realised through repeated mixing of the genes - here, washout probability is realised through repeated mixing of ideas. A small washout probability means that the idea does not lose its essence over repeated exposures to other ideas. Many reasonably good ideas share this feature. Most people can see the value of reasonably good ideas and wide exposure does not dilute them too much. The umbrella, shoes, and extension cords are all ideas that I imagine had low washout probability at the onset.

This is no longer true for fantastic product ideas, beyond the reasonably good. Fantastic products can sometimes start out as very obscure and unintuitive ideas. They only become obviously fantastic in hindsight. Renting your spare bedroom to a stranger when hotels exist (AirBnB), organising information on the young web when libraries exist (Google), and building complicated and fragile machines for transport when horses exist (Ford) are all ideas that would have had quite high washout probability at the onset. If they are less intuitive, they will meet more resistance when exposed to other people.

One reason why these product ideas became reality despite being unintuitive is the people behind them. The characteristics of a stereotypical founder (tenacious, single-minded, resourceful) can protect an idea and give it very low-washout probability. These characteristics make it very hard to stop a founder from pursuing their ideas no matter who they talk to, and if that’s true then it follows that there is a graveyard of fantastic product ideas that were washed out and never built because the would-be founders happen to not fit into this stereotype.

Is it necessary to fit into this stereotype in order to build successfully? Here is where building secretly can help. Doing so protects fantastic product ideas especially when the founder doesn’t fit the single-minded archetype. Instead of throwing the core idea out into the wild and hoping that you are immovable in your pursuit, building secretly effectively minimises washout probability by making sure the core ideas are not exposed to the wild before they are easily defended. This also forces thinking actively about what is shared with whom, it encourages intentional growth of your network of advisors, beyond friends and investors, and shifts the aim of sharing ideas from social bonding to actively distilling the most useful advice from specific people.

Over time, as the product is built up more and more, the historical energy put into it acts as a cap on washout probability to the point that secrecy is no longer needed – you’re already immovable if you’re heavily invested in the venture, secrecy won’t buy you much more. Until then, building secretly unlocks the insights of others selectively while still making sure you don’t get dissuaded prematurely. Of course it doesn’t hurt to minimise competitive risk along the way 5.

Thanks to Radhika Ravi and Ben Chaudhri for feedback on early drafts of this essay.

-

Linux is a family of open-source operating systems first released on September 17, 1991. It is built collectively by a global team of volunteers. Unlike Apple OS releases and Windows, it is entirely free and the basis of many popular services on the internet. ↩

-

Or negative selection of bad mutations. For a wonderful history of genetics as a science see The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee. ↩

-

This happens for two reasons, first, the mutation is quite rare, and second it has a 50% chance of not being passed on each time a child is born. So through repeated mating encounters, there is a rapidly diminishing chance that the Craig-mutation will survive a particular lineage - similar to the chance of a fair coin repeatedly landing heads. ↩

-

When it comes to building products, we tend to focus on usefulness much more than washout probability. Usefulness is much more intuitive to observe, clearly linked to success, and easily optimised. If your product is not useful, it is immediately felt by those in the target market – for example, building square wheeled cars to improve stability, or creating high-grip shoe laces to prevent them coming untied, in a world where velcro exists. This is something that can still be true even if some in the market deny it – it can present as an emperor’s-new-clothes-type delusion. ↩

-

An obvious advantage of building secretly is minimising competitive risk. This happens in two ways: protecting intellectual property – most important if your idea is easy to implement (e.g., stock market prediction), or raising barriers to entry. The second effect happens involuntarily as your potential future competition is left behind while you build the foundations you need to compete in this space – you keep them in the dark for longer. An example of a business with high barriers to entry are railroads. You need a factory, steel, land, and permissions to build tracks to get started, not to mention the deals with train companies who already connect core hubs. But if you’ve been amassing the knowledge, capital, and permission to start building tracks for years, it becomes very difficult to compete with you. By building secretly, you will have raised the barriers to entry for others who may have had the idea to build when you did, but delayed for whatever reason. ↩